Understanding Affordability Problems for Drinking Water and Sewer Utilities

Research results describe the location and extent of household stress in New Jersey. The cost of drinking water and sewage utility services has been rising faster than inflation since the early 1980s, creating household affordability stresses. Roughly one-fifth of New Jersey households may face affordability concerns. What does this mean for our ability to continue meeting public health needs and environmental regulations?

New Jersey has some of the oldest water infrastructure in the nation; after all, we are one of the original states and an early focus of industrialization. Much of our drinking water and sewer pipeline systems was developed in two major growth periods, from 1890 to 1930 (an addition of 2.5 million people, mostly in urban areas) and from 1950 to 1970 (3 million people mostly in the suburbs, with 2.3 million new residents and a shift of 0.7 million people from cities to suburbs). Much of this infrastructure needs major repair or replacement now (or soon).

These pipeline systems are linked to drinking water treatment plants and sewage treatment plants, which are more modern, as most have been upgraded over the years in response to new requirements and facility age. However, more upgrades will be needed in coming years to address emerging treatment needs, such as PFAS (the forever chemicals) in drinking water and combined sewer overflows and nutrients in sewer systems.

Finally, the customer base for drinking water and sewer utilities has been changing as New Jersey’s economy becomes more focused on finance and services and less on manufacturing. This trend shifts costs to households and commercial properties.

Affordability Stresses Increase

The result is increased utility costs for households. Nationally, drinking water and sewer utility costs have been rising faster than inflation since the early 1980s, according to USEPA and the Brookings Institute. In New Jersey, my intern Tianyi Luo recently completed a study of water rates for the years 2011 to 2019 at 26 major drinking water utilities in New Jersey, finding that 20 of them increased their rates faster than inflation during that period, with nine recording rate increases more than 30 percent above the inflation rate. These increases are also greater than recent changes in household incomes for many moderate- and lower-income households, creating affordability issues.

“Too many people assume that these utilities can provide high-quality services with low rates. The result in too many cases has been disinvestment in our water infrastructure. Protection of low-income households is a principled objection to rate increases. Resolving the affordability issue would help eliminate that objection, allowing for greatly improved infrastructure asset management.”

Affordability is a major focus of Jersey Water Works, a consortium of utilities, governments, agencies, environmental and community advocates, consultants, academics, and others that “is working to transform New Jersey’s inadequate water infrastructure through sustainable, cost-effective solutions that provide communities with clean water and waterways; healthier, safer neighborhoods; local jobs; flood and climate resilience; and economic growth.” Ninety percent of all New Jersey residents are served by drinking water and sewer utilities, making affordability a major issue for our densely developed state.

Increased investments in our water infrastructure will improve communities and can reduce utility costs in some cases (such as through energy efficiency), but for many utilities the result will be increased customer costs and—therefore—growing affordability stresses. Through its backbone staff at New Jersey Future and assistance from Rutgers researchers, Jersey Water Works has worked for several years to develop a methodology for understanding current affordability stresses. The methodology can be used to track changes over time and provide information that decision-makers can use to reduce household affordability stresses.

The Approach

Rate information was collected for nearly 600 drinking water and sewer utilities, representing roughly 90 percent of all households with such services. The methodology is an adaptation of the Affordability Ratio method developed by a colleague, Dr. Manuel Teodoro, now of the University of Wisconsin. Affordability is inevitably a somewhat subjective topic, but the Affordability Ratio method is quickly gaining acceptance as a useful approach.

The New Jersey approach compares the combined utility costs for a standard household (three persons using 45,000 gallons of water per year, based on New Jersey analyses) to the disposable income of households at the 20th percentile income level (i.e., 20 percent of households in that area earn less and 80 percent earn more). National practice in affordability analysis is increasingly focused on this income level, rather than the median income levels previously used, because households at this level are a better indicator of significant financial stress.

Disposable income is used instead of total income, because many household costs are not discretionary, such as housing, energy, and basic food levels. Where little discretionary income remains, high utility bills can force households to make damaging choices regarding health, food, and other critical needs.

The methodology then looks at how many households in each area (defined by Census tract, drinking water utility, and sewer utility) cannot pay the combined utility costs without exceeding a specific percentage of their disposable income. Three levels of stress are used, from Baseline (where water utility costs exceed 10 percent of disposable income) to Severe (30 percent). An important caveat is that the methodology assumes that all households pay their utility costs directly, which will not be correct for many renters and those who already receive government housing subsidies. As a result, the methodology provides an assessment of potential affordability stresses; real stresses may be lower or higher depending on local circumstances, existing household subsidies, actual household sizes and water demands, and so on.

A major benefit is that the study not only determines whether utility costs are affordable, but how bad the situation might be as well. This effort to assess the number of stressed households for an entire state—but at a very granular level—is new. We are not aware of another study with a similar approach.

The Results

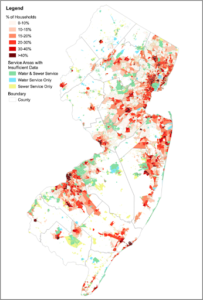

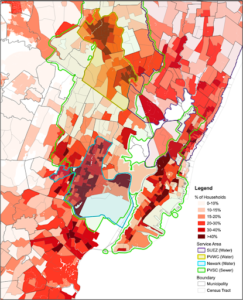

The project report shows clearly that affordability stresses are evident in most areas, including some that will surprise many people. Still, as expected, they are concentrated most heavily where low-income households are common. Statewide, roughly one-fifth (just over 20 percent) of all households fall into the Baseline Affordability Stress category, indicating that they would have difficulties paying their utility bills without harm to important parts of their household budget if they paid utility bills directly.

From the statewide map of the Baseline Affordability Stress results, the prevalence of areas with more than 10 percent of households is clear. Perhaps as important are the large variations within areas that might be perceived as demographically similar. Even in urban areas that might be expected to have high affordability stresses, some neighborhoods show distinctly different results, as demonstrated by the results for the Newark area.

What Happens Next?

There are many potential uses for the methodology and the current results.

- Trend Analysis: Jersey Water Works intends that this methodology be periodically used to track trends in affordability stresses. For example, the household income data used here was from before the COVID-19 pandemic; newer income data may provide very different results. Changes in utility rates and a better understanding of how existing and future household assistance programs affect household costs will also change the results.

- Utility Uses: Individual utilities can help reduce affordability stresses in several ways. First, how utility rates are set has a big impact on affordability. The balance between fixed charges (e.g., quarterly costs that don’t vary with use) and volumetric charges (based on water demands) can play a significant role in the costs to households that don’t use much water. Some utilities only have fixed charges, and so households pay the same amount no matter how little water they use or sewage they generate, which exacerbates affordability stresses. Second, drinking water utilities can help customers reduce their costs through water conservation and leak reductions, perhaps through programs that target low-income neighborhoods or high-volume users. Third, if the New Jersey Legislature passes proposed legislation (S4018) authorizing rate assistance for low-income households, utilities could create programs that help households not only during a short-term crisis but by addressing long-term affordability stresses as well. However, this approach will only be feasible for utilities with relatively low percentages of stressed households, where any rate impacts for other households would be limited. Utilities with high concentrations of poverty would not be able to address affordability concerns without drastic rate increases for the remaining customers, which would create a new group of stressed households.

- Statewide Programs: The State can also use these results in several ways. First, New Jersey can use existing or potential state and federal funding to target utilities with high affordability stresses, so that system upgrades and restoration have a lower net cost to customers. A good example is state funding for lead service line replacement in places like Paterson and Trenton. Second, state law could be modified to authorize low-income household rate assistance programs at the utility level, as already authorized for senior and military veteran households. Third, the State could create a long-term statewide program for drinking water and sewer affordability (analogous to existing energy assistance programs), which would relieve individual utilities of the need to develop individual programs.

- Neighborhood-level Interventions: Affordability for drinking water and sewer utility costs is just one part of broader affordability problems, due to both low incomes and higher costs. Governmental and non-governmental organizations can use these results to identify neighborhoods with high affordability stresses. Social services, job training, improved food access, and many other types of programs can be targeted to these neighborhoods. The objective would be to reduce affordability stresses by increasing incomes through better jobs and decreasing costs through better retail access, more energy-efficient housing, etc.

For the first time, New Jersey has access to a detailed assessment of potential household affordability stresses. We know from recent history that affordability issues have prevented utilities from establishing rates sufficient to properly maintain and improve their systems. Too many people assume that these utilities can provide high-quality services with low rates. The result in too many cases has been disinvestment in our water infrastructure. Protection of low-income households is a principled objection to rate increases. Resolving the affordability issue would help eliminate that objection, allowing for greatly improved infrastructure asset management.

1 Van Abs, Evans, and Irby. 2021. A New Jersey Affordability Methodology and Assessment for Drinking Water and Sewer Utility Costs. The report is available from Jersey Water Works at: https://www.jerseywaterworks.org/resource/a-new-jersey-affordability-methodology-and-assessment-for-drinking-water-and-sewer-utility-costs/

Daniel J. Van Abs is professor of professional practice for water, society, and environment at the Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences. He has 40 years of experience as a professional, manager, researcher, planner, educator, and advocate in the field of water resources management. The views expressed in this essay are solely those of the author and do not represent Rutgers University.